An end to all this prostate trouble?

The prostate gland causes entirely too many problems. In the US, prostate cancer kills about one man of every forty. “Benign prostate hyperplasia” (BPH) is even more common, affecting most men over age 60. It pinches the urinary tract, making it hard to urinate, and is constantly in danger of transforming from “benign” to “malignant”. Even the difficulty urinating is enough of a problem that men often get surgery for it, usually TURP, a sort of roto-rooter job (except cutting through the pipe instead of just cleaning it out).

In women, breast cancer has a similar death toll, but the breasts have an excuse: they’re much bigger; there are many more cells to go bad. They’re also much more metabolically active, capable of producing enough milk to feed a baby; the prostate’s output is tiny in comparison.

One idea I’ve seen is that the prostate serves as the body’s “gatekeeper” against sexually transmitted diseases, and in the process often gets chronically infected itself; the resulting inflammation may cause hyperplasia, first benign then malignant. Infectious causation is too often neglected these days, and sexually transmitted diseases are common, so this is not unreasonable. But it doesn’t seem like a great explanation. The prostate doesn’t filter the urinary tract; it just secretes into it; there’s no real “gate” there to be “kept”. The prostate’s position is like that of the salivary glands, which are not known for being great houses of cancer. And the epidemiology backs this up: correlations with STDs are there, but not huge. The odds ratios are between one and two; in comparison, the odds ratio for human papillomavirus and oropharyngeal cancer is greater than ten. An odds ratio of ten should make the ears perk up; an odds ratio of 1.5 can be a minor effect or can be just a spurious correlation. And with the prostate, there’s not just a minor effect which needs explaining: there has to be some major-league cause.

A decade ago, Scott Alexander, in his blog “Slate Star Codex”, wrote:

“About five years ago, two Israeli doctors named Gat and Goren posit the theory that benign prostatic hyperplasia, a prostate disease that affects millions of older men, is caused by incompetence of the spermatic veins. They claim they can treat it surgically, and show off rows of smiling patients with glowing testimonials. Once again, the guys are good doctors, nothing about their theory contradicts basic laws of biology, and no one else has any better ideas.

I shamefacedly admit I want this one to be true. There’s so much “well, everything is a complicated combination of genes, biomolecules, biopsychosocial stressors and immune modulators that we may never really understand” going on in medicine today that it would be super gratifying if this one mysterious disease turned out to just be plumbing going in the wrong direction. And although the prostate is about as far from my area of expertise as it is possible to be, I have to say that from a physiological standpoint their theory seems to have that rare and much-sought scientific elegance, where everything comes together in a pretty package.

As far as I can tell, the medical community has totally ignored this one. Gat and Goren have published their hypothesis and their apparent excellent results in peer-reviewed medical journals. It has garnered praise from prestigious figures in the field (bonus points for calling it “seminal”, especially if the pun was intentional). As far as I know, no one has attacked it or even formally expressed doubt. Yet as far as I know, it has gone nowhere.

Does everyone mutually assume that if something this revolutionary were true, someone would have noticed beyond a single article in a urology journal? Do they just decide it needs further research, and hope that this research will be conducted by someone else? Or do they think that it would end up like Zamboni’s MS cure, with hundreds of thousands of dollars wasted, dozens of unnecessary surgeries performed, and nothing to show but yet another fringe medical idea that sounded good at the time?

I read that some time after it was written, and found that there’s since been a small confirmatory study from Germany. So it hasn’t been entirely neglected. Gat and Goren also have other papers in the area. (The latter author is sometimes listed as “Gornish”, that being the non-Hebraicized verson of his name.)

At any rate, Scott’s was more of a social view of the question than a technical one. Still, it was intriguing enough to get me to read the papers he linked to, and then to read the authors’ other papers on the subject. I found that the above language does not convey the full scope of the theory. This is not just about BPH; it’s also about prostate cancer, and also about varicocele, the top cause of male infertility. And it promises to eliminate all these problems, if caught early enough, which is not hard: screening for it is simple and cheap.

The theory here is largely mechanical; and it’s not just psychiatrists like Scott who are weak at mechanical explanations; it’s doctors in general as well as medical researchers and biologists. There is even a famous paper “Can a Biologist Fix a Radio?”, wherein the biologist author laments the unsuitability of biological reasoning, at least of the usual sort, for the task of fixing an old radio. (End result: “the radio remains broken.”) Reading medical review papers, I have often gotten quite disgusted at the way they list result after result in the fashion “X has an effect on Y”, without saying what the size of the effect is or even what dose of X is required. Especially when you want to chain two mechanisms together (X having an effect on Y and then Y having an effect on Z), you’ve got to know the numbers. The convention is that p=0.06 means “it doesn’t have an effect” and p=0.04 means “it has an effect”, but any real thought requires more than just that binary view of things.

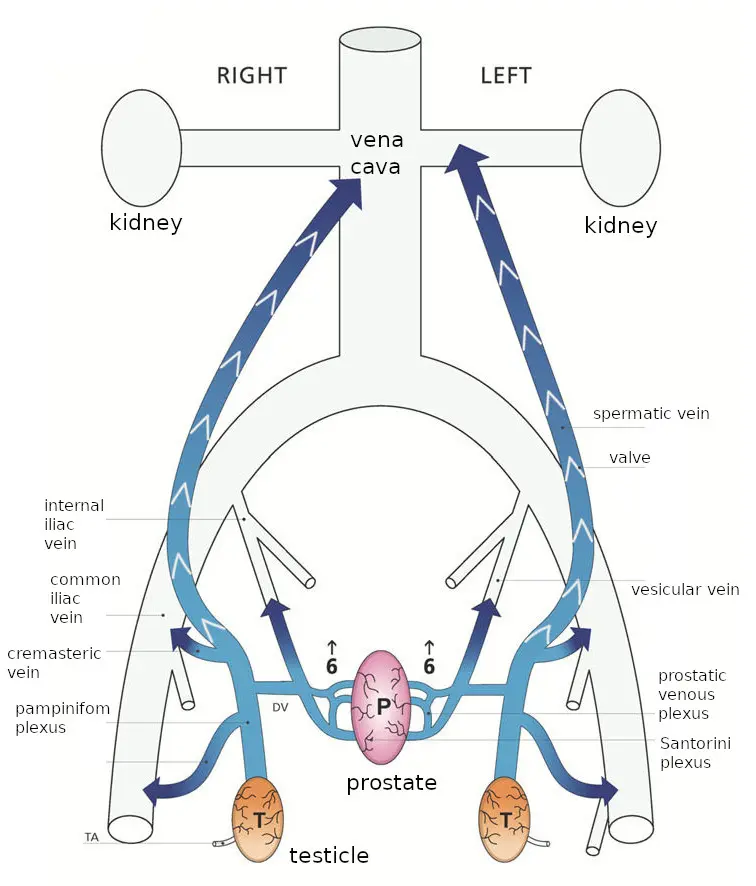

I’m thoroughly comfortable with mechanical theory and practice, so here’s an attempt at a full rendering of the Gat/Goren theory, in language as simple as the subject permits, followed by my own comments. The basic idea is this: in healthy men, blood flows out from the testicles into the spermatic veins (of which there is one for each testicle). Each spermatic vein goes up vertically inside the body until it’s near the kidney on that side. (The kidneys are about halfway up the back.) The left spermatic vein then feeds into the left kidney vein, while the right spermatic vein feeds directly into the vena cava (the vein “as big as a cave”; it’s the largest vein in the body, leading directly back to the heart; the kidney veins also feed into it). Each spermatic vein has about seven one-way valves to prevent blood from flowing the wrong way through the vein, which it would otherwise do due to the force of gravity. The following diagram from their latest paper shows the situation in healthy men. (That paper is under a Creative Commons license, which this re-use is in accordance with; I’ve slightly altered their diagram to un-abbreviate the labels. The subsequent images are also re-used under the same license.)

With age and wear and tear, the one-way valves cease to function, and blood does flow the wrong way: down the vein towards the testicles. It bathes them in poorly-oxygenated blood, which is bad for them, eventually killing the germ cells which produce sperm and causing infertility.

The medical literature often blames that infertility on the warmth which is produced by that reverse blood flow, but Gat and Goren blame the low oxygen: warmth does interfere with sperm production, but it’s low oxygen that actually kills sperm-producing cells, as occurs in men with this disorder. (The warmth is still quite useful for diagnosing the disorder since thermal imaging shows it plainly.)

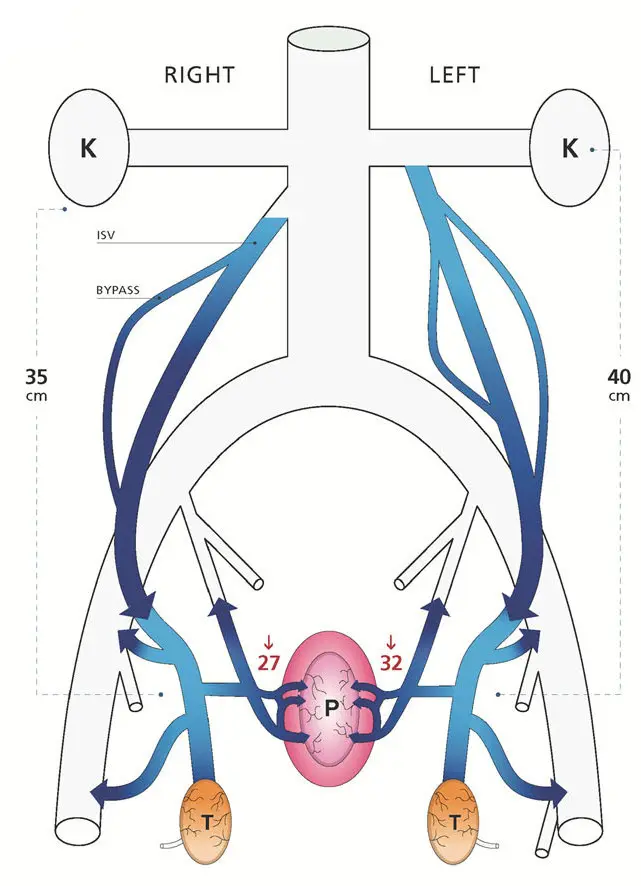

The blood from the testicles, still at higher than normal pressure, then continues on out the network of veins in that area, and spills into the prostate, going backwards through veins that normally drain the prostate; to use their diagram from the same paper:

Since this blood has just left the testicles, it is heavily loaded with testosterone, which promotes prostate growth. Making things even worse, that blood has a much higher than normal percentage of free testosterone. Normally the vast majority of testosterone in the blood is bound to sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG); only a tiny proportion is free, but that proportion has the actual hormone effect. In the testicular flow, there isn’t enough SHBG to bind to all the testosterone; that happens only on the way back to the heart when it is mixed with the blood returning from the rest of the body. So the total effect is to hit prostate cells with about a hundred times the normal dose of free testosterone. This makes them grow; their growth is called benign prostatic hyperplasia or prostate cancer. There’s also another effect of the high pressure: swelling the prostate (pressurizing it and expanding it). It also swells the veins in the scrotum, the “pampiniform plexus” above the testicles; when that swelling is prominent enough, it is given the name “varicocele”.

(I’d originally imagined that their reason for the high free testosterone was that the testosterone molecules took time to find the SHBG molecules and bind to them, but that process seems to be too fast: this study found a half-life of 12 seconds for dissociation, and at equilibrium the rate of association must equal the rate of dissociation. So overwhelming the local supply of SHBG seems like a better explanation, though being out of equilibrium might add to it a bit.)

This theory can explain why giving men testosterone doesn’t seem to increase the risk of prostate cancer, despite testosterone promoting prostate cancer. Giving men testosterone shuts down their own production of testosterone, making backflow from the testicles to the prostate harmless. Thus even with more testosterone in their blood, they can have less in the prostate gland.

It can also explain why low testosterone is correlated with prostate cancer: the backflow damages the testicles via hypoxia, lowering testosterone, while simultaneously funneling the testosterone that still is released directly to the prostate.

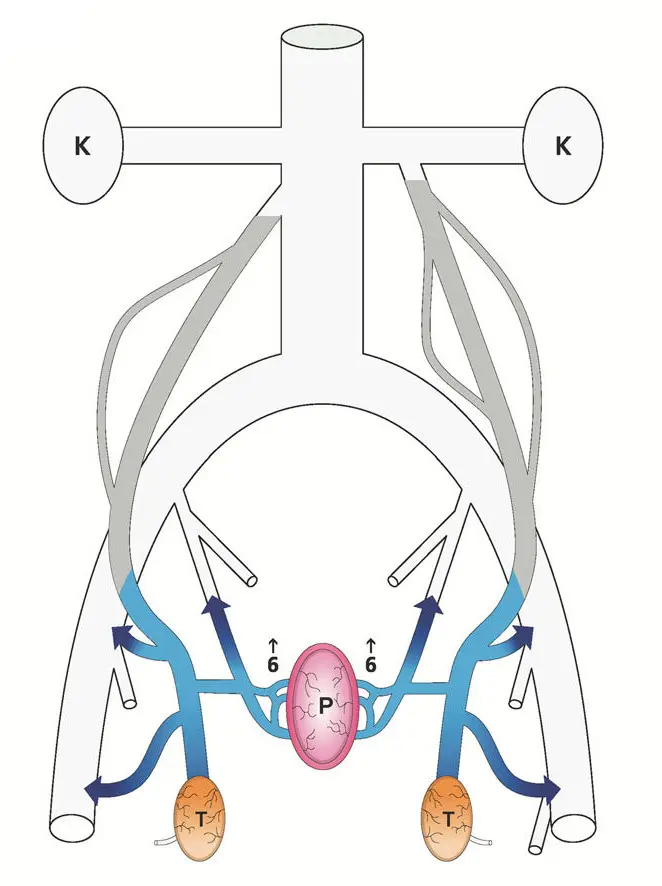

The way Gat and Goren fix this is simply by destroying the spermatic veins. Under fluoroscopy (that is, viewing an X-ray image continuously during the procedure), they snake a catheter in through the veins until it gets to the top of the spermatic vein. They then inject a pulse of X-ray contrast agent to make the flow in that vein visible under the fluoroscope, proving that the flow really is going the wrong way. Having done so, they then have the patient close off the bottom of the vein with finger pressure while they inject a sclerosing agent into the vein; they start by moving the catheter to the bottom and sclerosing that portion, then repeatedly withdraw the catheter a bit (moving up) and inject more. After a few minutes the vein is thoroughly and permanently clogged. This is their diagram of the results:

To say a bit more about the background of this theory, venous circulation is not a one-path-only thing: the veins are not like a tree, where there’s only one path from the trunk to each leaf. Indeed, this multiplicity of paths is why the problem arises in the first place: the testicles being drained both by the spermatic veins and by the local circulation. It’s also why it can be solved in this manner: the remaining veins enlarge a bit to accomodate the flow, as well as new veins growing. But it’s also why they need to be thorough when performing the procedure. Besides destroying both spermatic veins (a weakness, Gat and Goren say, of other doctors’ work, where it’s often only done on the left vein where the swollen veins tend to be more prominent), they also follow up by injecting more pulses of contrast agent to make sure that there’s no collateral circulation bypassing the blocked vein, and that the veins they did treat are really blocked. (The finger blocking the vein at the bottom keeps the sclerosing agent where it belongs rather than letting it spread further into the body. Of course a little of it still spreads, but the sort of agent they use is harmless at low concencentrations.)

It’s odd for there to be such an easily-removable design flaw in the human body; evolution tends to remove them. Since it strikes at advanced ages, BPH doesn’t make a big impact on a man’s ability to pass on his genes. But being the leading cause of male infertility sure does. Their explanation is that evolution hasn’t had much time to work on the problem; in animals the spermatic vein is horizontal, and doesn’t have or need one-way valves. It’s our standing upright that yields the problem; in evolutionary terms that’s a recent development.

So that’s their theory. There is an obvious question, though, which mechanically-inclined reviewers might have raised, and which deserves an answer. It has to do with pressure and height. As Gat and Goren say, it is a law of physics that pressure within a fluid increases as one descends deeper into the fluid, in direct proportion to the depth. (They invoke Bernoulli’s equation, which also involves the velocity of the fluid, but they then assume the velocity is negligible, so are using only the part of the equation that relates pressure to height.)

But they apply this law only to the blood in the spermatic vein. It is also applicable to the blood in the arteries and to the blood in other veins. Doing so, though, would ruin their argument: it would mean that although pressure increases as one descends down the spermatic vein, it also increases in the other veins. In their account, blood goes backward through the spermatic vein, emerging at a pressure of 40 cm H2O or so, then pours into other veins which, drained by the common iliac vein which in turn is drained by the inferior vena cava, are at less than 10 cm H2O. (They use mm Hg as their units, but I’ll be converting all pressures to cm of water, since it’s a more directly relevant unit: blood’s density is close to that of water.)

But gravity acts also on the iliac vein and the vena cava! In general, if you have a loop of tubing in a gravitational field, and the fluid inside is not in motion, the pressure of the fluid is everywhere proportional to altitude, no matter how the tubing is shaped. No spontaneous circulation arises. Here we have a loop with the spermatic vein being on one side and the vena cava and iliac vein on the other, connected on top and bottom, and the claim is that this is enough to give rise to spontaneous circulation. It’s not.

Yet there is reverse flow in the spermatic vein when the valves fail; that’s standard medical knowledge. And, as mentioned, Gat and Goren confirm the reverse flow by injecting tracer dye into each and every vein they treat, before sclerosing that vein. The reverse flow exists; it just has to have a more complicated explanation than the one they provide.

Another part of their argument is that venous blood infiltrates the prostate due to the venous pressure exceeding the local pressure in the arteries that feed the prostate. But gravity also acts on the blood in arteries. If the local arterial pressure were equally boosted by height, it could not be exceeded.

Fortunately for their argument, that’s not the way the human body works. It sort of theoretically could work that way, if all the blood vessels were rigid: pressure everywhere would increase with decreasing altitude in the same way that pressure increases with depth inside the ocean. Relative pressures would be higher in arteries, lower in veins, and intermediate in capillaries: the pressure difference between artery and vein would be the same throughout the body, but the pressures of both would be highest in the feet and lowest in the head. (For fish, or babies in the womb, this works even without blood vessels being rigid, due to the outside pressure varying with altitude in the same way as the pressure in their blood vessels does; all the fluids involved have densities close enough to the density of water that the difference doesn’t matter.)

Of course in fact blood vessels are not at all rigid. Arteries are the closest to being rigid; they’re thick-walled and can take a lot of pressure, though they still have an important amount of elasticity. Veins, though, are thin-walled: they swell up with higher pressure and collapse flat at negative pressure. Capillaries don’t swell, but at higher pressures they leak fluid into the surrounding tissues, producing swelling there. So the body maintains capillary pressures in the neighborhood of 20 cm H2O (somewhat higher at the start of the capillary and somewhat lower at its exit).

The usual figures for blood pressure (the ones for which “normal” is about “120 over 80”) are arterial pressures in units of mm Hg, measured with a blood cuff around the arm (at about the same altitude as the heart). In that example, the 120 is the maximum pressure just after the heart beats, and the 80 is the minimum pressure it reaches between beats. Those numbers translate into about 160 cm H2O and 110 cm H2O.

In a standing person, the arterial blood pressure is considerably higher if measured at the ankles, as it would be in the rigid-vessel model. But then as large arteries divide down into smaller and smaller arteries, most of that pressure is spent before it gets to the capillaries. This is not just a matter of passive friction but also of active control: arteries have muscular walls and contract to restrict blood flow to the part of the body that they feed. When more blood flow is needed somewhere, the local arteries relax to let it through.

Veins operate at low pressure, usually less than 15 cm H2O; the hard part, and the part that is most relevant here, is explaining how they get blood upwards against gravity, since their pressure is nowhere near enough to do so. The one-way valves in the spermatic vein have already been mentioned, and are present in many other veins too, but valves themselves don’t do any actual pumping work (in the physics sense of the word “work”). Yet work needs to be done to pump blood uphill. In most cases that work is supplied by muscle movements in nearby muscles, which compress the veins. In engineering, pumps are often built with two one-way valves, the volume between those valves being alternately compressed and expanded; the principle is the same here. But since it relies on muscle movements which are made for other purposes, this process is slow and uncertain. So to get the same throughput the veins are much wider than the arteries.

When the veins’ one-way valves fail near the surfaces of the legs, it results in high pressures and swollen, unsightly “varicose veins”. Even with functioning valves, standing motionless results in high venous pressures in the feet; thus the advice, on long trips sitting down, to take breaks and to move the feet and legs around, so as to avoid blood stagnating and clotting (a “deep vein thrombosis”). For blood circulation fidgeting is good, even if it’s not “good manners”.

But the vena cava is different: it doesn’t have any valves; neither does the iliac vein (at least the portion of it under discussion here). Yet somehow blood which feeds into it at low pressure manages to climb to the heart, overcoming that 40 mm H2O pressure difference and more.

I looked in the medical literature for how this actually happens, and was disappointed not to find a clear, definitive answer. It’s common to see it stated that breathing has an effect. The heart is located between the lungs, so shares a common pressure compartment. The pressure outside the heart is about the same as the pressure outside the lungs. That pressure decreases to inhale and increases to exhale. But those pressure excursions are minor: about 1 cm H2O in either direction. (This rises with heavy breathing, as in exercise; but the blood circulation has to work even when the body is calm.)

There is also a disturbing level of confusion in the medical literature as regards what “zero pressure” is. Good engineering practice is to say what reference pressure one is measuring against. Commonly that is the ambient pressure (the pressure of the air surrounding the body, which is about 1000 cm H2O at sea level and lower at higher altitudes). To inhale, one obviously has to drop the pressure in the lungs below ambient pressure. A measurement relative to ambient pressure is called “gauge pressure” by engineers, because it’s what the usual sorts of pressure gauges tell you. The old-fashioned mercury manometers for measuring blood pressure measured gauge pressure, since they were open to the air on their other end. Modern mercury-free manometers are no doubt built to give the same numbers (so as to be compatible, and also because it’s easy to build a gauge that way.) So the usual arterial blood pressure numbers are all referenced against ambient pressure.

That is so even if medical literature tries to confuse the matter, as happens. Take, for instance, this passage in Guyton and Hall’s Textbook of Medical Physiology, 14th edition (a standard text in medical schools):

Pressure Reference Level for Measuring Venous and Other Circulatory Pressures Although we have spoken of right atrial pressure as being 0 mm Hg and arterial pressure as being 100 mm Hg, we have not stated the gravitational level in the circulatory system to which this pressure is referred. There is one point in the circulatory system at which gravitational pressure factors caused by changes in body position of a healthy person usually do not affect the pressure measurement by more than 1 to 2 mm Hg. This is at or near the level of the tricuspid valve, as shown by the crossed axes in Figure 15-12. Therefore, all circulatory pressure measurements discussed in this text are referred to this level, which is called the reference level for pressure measurement…

When a person is lying on his or her back, the tricuspid valve is located at almost exactly 60% of the chest thickness in front of the back. This is the zero pressure reference level for a person lying down.

Now, what is meant by that? It purports to define a pressure reference level, and one that is not just equal to ambient pressure. But does it mean that every single blood pressure measurement in the entire book was done by snaking a catheter into the heart until it reaches the tricuspid valve, and using that as reference? Of course not! That would be ridiculously dangerous and expensive. Also, that valve is in the middle of the heart: it’s the valve between the right atrium and the right ventricle. The pressure there varies strongly as the heart beats, making it unsuitable as an experimental reference pressure.

So the passage cannot really mean that it is defining a reference pressure. Instead it is defining a pressure reference altitude. I take it to be just an overly fancy way of standardizing the practice of putting the blood pressure cuff around the top of the arm with the arm draping normally down the side of the body, which puts the cuff at about heart height. (Even on someone lying down, that position of the cuff is still at about heart height.)

Unfortunately it also betrays a lack of real precision, which is probably unimportant as regards the usual use (arterial pressures), since those numbers are large, but is important when dealing with the much lower pressures in veins and the issue of how venous blood is pushed back from the lower body to the heart.

This lack of a definition also extends to the Gat and Goren papers: they give pressure numbers, but never say relative to what. Ambient pressure generally seems like the best reference pressure to use; I will be hoping that papers I cite for pressures used it, but also, since none of them say they do, not placing much trust in any absolute numbers.

Enough complaining; time to return to the question of how blood makes it back to the heart. As mentioned, inhaling a breath reduces the pressure in the heart and lungs; but that reduced pressure ends at the diaphragm, the sheet of muscle and tendon that separates the thorax (heart and lungs) from the abdomen (guts). The diaphragm is arched upwards; to inhale we contract it, flattening it and lowering the pressure in the heart and lungs while increasing the pressure in the abdomen. Those two pressure changes add together to force blood in the vena cava up past the diaphragm toward the heart. (This is for normal breathing; in general the pressure in the abdomen can vary quite considerably depending on what the abdominal muscles are doing, as measured for instance in this paper. Above the diaphragm, it also depends on what the rib muscles are doing, they being another force that powers breathing. But in normal breathing the diaphragm is the main actor.)

So breathing helps as regards the general problem of returning blood to the heart. Still, the heart does need blood feeding it when breathing out as well as when breathing in. We don’t synchronize our breaths with our heartbeats, nor could we, since breaths are less frequent. (The frequency of the heartbeat does change a bit in breathing out compared to breathing in, though.)

It helps that the lungs are elastic, and would collapse if there weren’t more pressure inside them than outside. This means the normal pressure in the thorax is negative, helping to pull blood in. This “transpulmonary pressure” (the difference between the air pressure in the lung and the fluid pressure outside it) is about 6 cm H2O.

The heart, as it relaxes from its contraction, presumably also can exert a bit of suction on the incoming flow; it’s obviously not rigid enough to exert much suction, but every little bit helps.

That the system operates right on the edge, getting blood back to the heart with almost no pressure to spare, can be seen by the reader if he examines the veins on the back of his hand: if held at lap level those veins stand out, full of blood, while if raised to eye level they flatten. By moving the hand up or down slowly, giving the veins time to empty or fill, the level where the transition from full to flat occurs can be determined; it’s about at the same level as the heart. (This demonstration probably won’t work for everyone; blood vessels are less prominent in the young, and also can be hidden by fat.)

Now to return to the main question here, which is backflow in the spermatic veins. Those veins are entirely below the diaphragm. They are in the same pressure compartment as the vena cava is at that altitude (the retroperitoneal space), so the two competing flow paths are under about the same pressures.

I’m afraid that the answer is that Gat and Goren are simply wrong about the pressure at the bottom of the vena cava when standing: it must be at considerably higher pressure than the sub-10-cm H2O that they say it is – or at least it is when the patient is standing up (or sitting normally). It’s an understandable error, since the medical literature usually refers to the lower numbers: in circumstances where it matters, patients are commonly horizontal.

I found a paper from 1966 which measured intravenous pressures both with the patient horizontal and with the patient standing: the horizontal numbers are in accordance with Gat and Goren’s, but the standing numbers are considerably higher. Using their numbers for the common iliac vein (since they don’t say where in the vena cava they measured pressures, and since the common iliac vein is where the veins from the prostate enter, so is the most relevant number anyway), the average of their three measurements has the pressure with patient horizontal as 8 cm H2O (plus an additional 9 cm H2O when breathing in), and the pressure with patient erect as 30 cm H2O (plus an additional 15 cm H2O when breathing in). If we accept these numbers, the pressure in the common iliac vein is close to the pressure in the bottom of the spermatic veins.

Again, though, it’s generally agreed that the backflow exists, at least through the spermatic vein. (Gat and Goren’s contribution is extending it to the prostate.) The large pressure difference they say is driving the backflow is calculated based on improper assumptions, but there must be some pressure difference driving the backflow.

Now, one difference between the two veins competing for flow here is that the vena cava is much larger and thus has much less frictional resistance to flow. In general, blood flow in the body is dominated by frictional effects (fluid friction, that is, aka viscosity): Gat and Goren cite Poiseuille’s equation for fluid flow, which states that flow is proportional to the fourth power of the diameter of the pipe. In comparison, if friction were zero, the flow would only be proportional to the square of the diameter of the pipe (that is, proportional to its cross-sectional area). But Poiseuille’s equation, which has it as the fourth power, is the generally-accepted formula for blood flows. It’s just an approximation, not a fundamental law, but the fact that it’s the accepted approximation shows how dominant friction is in blood flow.

The ratio in diameters between the spermatic vein and the vena cava is about a factor of 7. So if equal lengths of the two veins are subjected to the same pressures, Poiseuille’s equation says that the vena cava has 2401 times the flow and 49 times the average flow velocity. But that just predicts much less forward flow in the spermatic vein; it does not predict that it backflows.

Yet it does. The hydrostatics don’t predict it, though; we need to look into its hydrodynamics. The two main sources of dynamic behavior (pulsations or fluctuations rather than constant flows and pressures) have already been mentioned: one is the right atrium, alternately accepting inflow then contracting in the heartbeat, its input valve slamming shut to prevent backflow. The other source is the breathing.

Since intestines have basically nothing holding them in place (as can be attested to by any hunter who has gutted an animal, slitting open its belly and seeing the guts spill out), it’s not just the blood in the veins but the whole abdominal compartment that is reasonably well modeled as having a pressure gradient determined by altitude: about one cm H2O pressure for every cm of altitude (since most things in the body have a density close to that of water). Of course pressures inside a pressurized cavity (such as the bladder, a vein, or an intestine) can be higher, but even within those cavities there is the same pressure gradient with altitude (unless filled with air or some other gas, as intestines sometimes are).

Though I earlier alluded to the retroperitoneal space as a pressure compartment, the peritoneum is a thin membrane which, in surgery, tears easily; there’s not much chance of it holding significant pressure for long. What mainly holds in abdominal pressure are layers of muscle and connective tissue. In the bottom of the abdomen this is the pelvic floor muscles. In men, those are just below the prostate, so the prostate too is in the same pressure compartment.

What isn’t in that pressure compartment are the testicles; they are hanging out in the breeze, surrounded by ambient pressure.

The level of influence that the heart’s beating has on the pressure in the vena cava can be judged by the velocity of flow in it. According to measurements done in this paper, the velocity in the inferior vena cava peaks at 45 cm/second (in people breathing normally while lying down, and measured at the level of the T11-T12 intervertebral disc). Per Bernoulli’s equation, that energy density is the same as is produced by a pressure rise of 2 cm against Earth’s gravity. (This is also the height an object rises to if it is thrown upwards with that speed.)

2 cm H2O is not much pressure rise, particularly compared to the above-cited 15 cm H2O pressure increase in the abdomen for breathing in. Also, the pressure pulse from the heartbeat is entirely inside the veins (and diminishes with distance from the heart), whereas the 15 cm H2O pressure increase is applied to the whole compartment uniformly. (But neither of those numbers is particularly certain, and both must vary considerably depending on circumstances.)

As mentioned above, capillaries and veins can only hold limited blood pressure. But what matters is the difference between external and internal pressure. If capillaries exceed maybe 40 cm H2O, they leak fluid, producing edema; but inside a pressure compartment at 30 cm H2O that internal pressure limit increases to 70 cm H2O. Numbers like those occur near the bottom of the abdominal cavity when standing: pressures higher all-around without producing distress. But if the testicles, which are outside that pressure compartment, experience the same internal pressure, that will produce distress in capillaries and veins.

While intact, the spermatic vein is protective: its one-way valves mean that blood is drawn upwards when the abdominal pressure is at its minimum and can’t return when it’s at its maximum. Still, to get into the abdomen at all, the blood in the spermatic vein has to be at least at the pressure of the abdomen (at the point of entry, which here is near the bottom of the abdomen). The abdominal pressure varies; if the pressure in the spermatic vein is between the minimum and the maximum abdominal pressures, then the part of the vein which is in the abdomen will be collapsed part of the time, which with intact valves makes for effective pumping. If the pressure in the spermatic vein is above the maximum abdominal pressure, it doesn’t need pumping to flow, but still functions as a pump, via the vein expanding and contracting.

So when the one-way valves fail, the pressure at the bottom of the spermatic vein increases. Still, the difference in pressure between the failed and working states is not the full 40 cm H2O that Gat and Goren deduce from the height of the spermatic vein, but rather cannot be more than the 15 cm H2O pressure difference between breathing in and breathing out.

Now, that last number is just a measurement from one paper, likely from one single Irishman; and if he had been breathing harder the number would have been higher. So it should not be taken as gospel; but it wasn’t easy even finding that number. Not that I pretend to thoroughness; I could well have missed a better source, and readers who know of one are invited to provide it. But I’ve spent enough time looking that at this point it seems like it might be easier to measure intra-abdominal pressure changes myself, sticking a pressure probe up my butt – that’s literally how this paper did it (but on horizontal patients rather than vertical ones, so their numbers are not quite on point here.) That’s not quite the same thing that the Irish paper measured, which was intravenous pressure; sticking a catheter into my veins is way beyond my skill set. But for measuring pressure increase it’s close enough, since the pressure increase from breathing is applied to the whole compartment.

In any case, that’s why there’s higher pressure at the bottom of the spermatic vein when the valves fail, but it doesn’t answer the question of why there is backflow. The situation, again, is of two vertical veins, connected at top and bottom, in the same pressure compartment, with one vein being much larger than the other. Static, constant flow would just be divided between the two; both would flow upwards. But consider rhythmically varying flow, such as is produced by the heartbeat or by breathing. First there is an acceleration phase, which acts on both veins. In the vena cava, with much less friction, the blood accelerates upwards, whereas in the spermatic vein, with more friction, there is much less acceleration; the extra upwards force is mostly spent against friction. Then there’s a deceleration phase. The blood in the vena cava has inertia; it’s trying to go upwards but has to stop, so the pressure at its top increases. Some of that higher-pressure blood then is pushed down the spermatic vein. And the flow up the vena cava has such a dominant share of the overall flow that even a slight influence like this can yield net backflow in the spermatic vein.

Now, the mechanism I just described does not seem like a particularly strong mechanism; but as mentioned, in practice it’s well established that there is backflow; this is just one way that theory can agree with that observation. There may be other mechanisms that do better, perhaps involving the portion of the flow which is outside the abdominal pressure compartment, and/or the relatively narrow veins communicating between the two paths at the their bottom – though that gets complicated enough that it’s not easy to think through; a computer model might be in order.

More questionable, although still quite plausible, is the idea that the backflow reaches the prostate. The Gat and Goren theory is that it is pushed by about 40 cm H2O pressure, overwhelming even the prostate’s arterial supply. But that’s pure theory; they don’t report actually measuring any pressures. (If they were researchers I would ding them harshly for not doing the measurements, but they’re clinicians; they’re paid to cure patients, not to produce knowledge.)

Gat and Goren didn’t do a great job of proving experimentally that backflow reaches the prostate, either. They measured the high free testosterone levels described above, but that measurement was at the bottom of the spermatic vein; they didn’t have their catheter make another turn and go into the deferential vein and then past its junction with the vesicular vein and into the vein coming from the prostate, so as to measure high free testosterone levels in a place where they definitely don’t belong. (This is readily excusable: those other veins are much smaller, so the catheter might not fit or might not be able to make the sharp turn into the smaller vein. Again, researchers should be dinged for omitting such tests – there’s got to be some way to measure pressures there – but clinicians get a pass.)

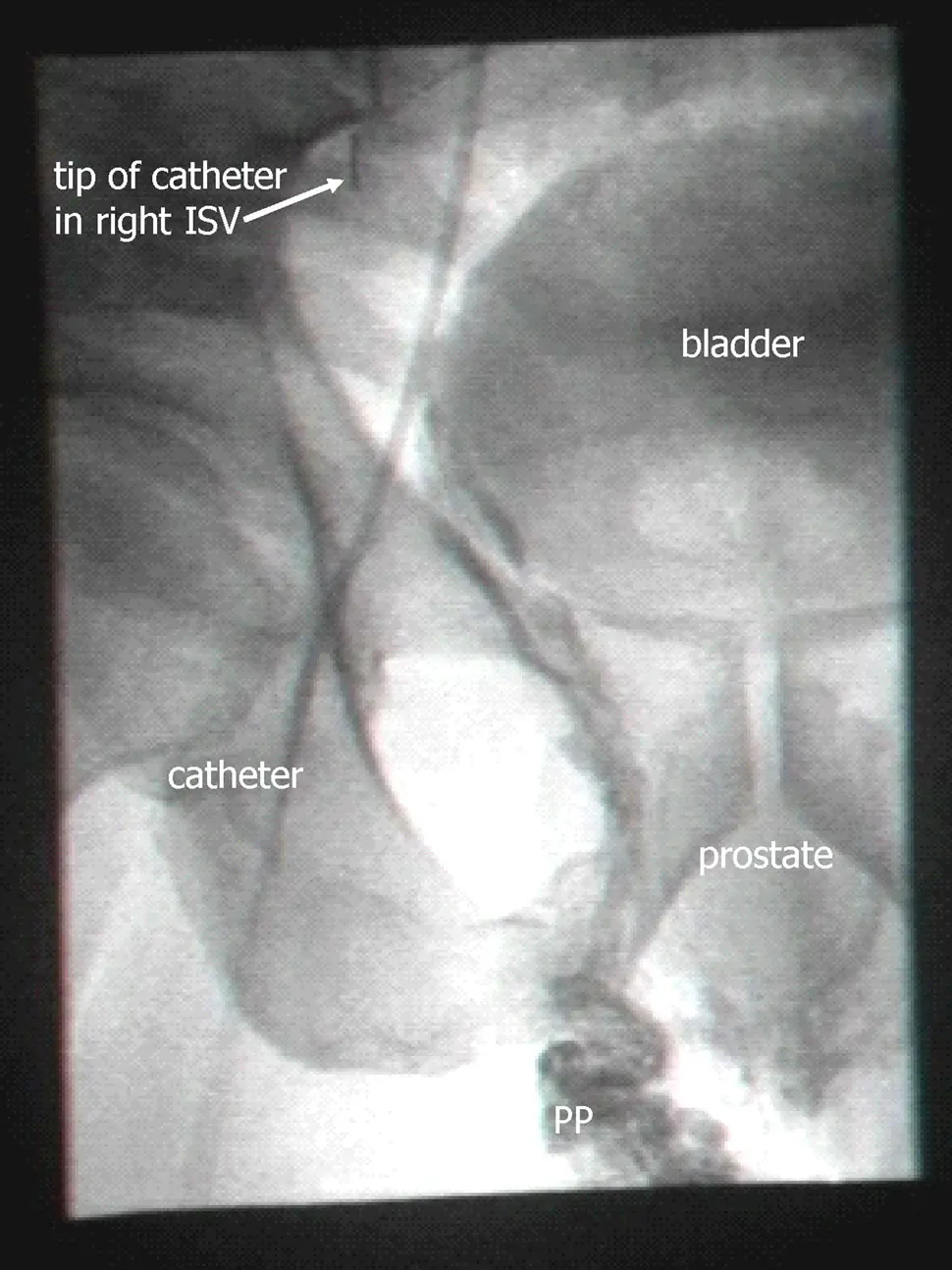

Perhaps the strongest piece of evidence they offer for backflow to the prostate is an X-ray showing contrast agent which was injected into the spermatic vein. They state that:

On retrograde venography of the PP, after a delay of about 10 s, a contrast material ‘blush’, of the prostate gland capsular region, was observed (Fig. 3). Both are clearly seen in the image.

Here’s their Figure 3 (again, reproduced from their most recent paper under the terms of a Creative Commons license):

Looking at it, I can see the oval they label “prostate”, but it’s pretty faint. There are various other structures (such as the bladder) which are also visible with similar intensity. Backflow down the spermatic vein is clearly visible (all that darkness going down to the region marked PP, for “pampiniform plexus”, the network of blood vessels above the testicle), but backflow down the spermatic vein is not the new part of their theory. There is some darkness under the the prostate, which looks like backflowing dye, but is not clearly connected to the dye in the PP region. Even if it is dye, it’s not evident whether it gets into the prostate itself. Perhaps specialists who are used to viewing fluoroscopy images will pronounce this one definitive, but for me it’d take a movie showing contrast emerging from the tip of the catheter and then making its way to the prostate; in this day and age, movies should be easy to provide. Of course in their clinical practice they are seeing such a movie with their own eyes for every patient, so it requires a modest level of distrust to doubt them on this. But it’s not entirely unknown for doctors to succumb to wishful thinking, and “blush” is not a strong word. I’m not inclined to distrust them on this, but the image they show is less than a complete proof.

I’d also be curious, with such a movie, to look for variations in the flow. There would no doubt be motion visible from breathing, and the contrast agent would show how that correlated with blood flow in the veins.

Breathing would help spread the testosterone-loaded outflow, since the prostate is inside the abdominal pressure compartment while the testicles are outside. Breathing would thus push the flow alternately in one direction then the other, increasing the chance of subjecting the prostate to outflow from the testicles. The movie would show this. Even if it resulted in only a weak and diluted flow which didn’t deliver the theorized hundred-fold increase in free testosterone, a ten-fold increase is still quite a lot and even a doubling would be important.

A really thorough experimental workup would measure all the relevant flows and pressures, perhaps by using an intravenous catheter loaded with multiple pressure and flow sensors each delivering many measurements per second. (Whether such a catheter can be bought today and whether it can be readily inserted into the veins in question are not matters I have looked into, but with modern technology there’s got to be a way of measuring such pressures.) Testosterone levels would also be measured at various points.

Recently a paper by Alyamani et al came out which did do such measurements of testosterone. The patients were 266 men undergoing prostatectomies for prostate cancer, none of whom had any prior hormonal therapy. During the course of those operations the researchers extracted blood from the prostatic dorsal vein and tested it for testosterone. They also tested the removed prostates for testosterone. They indeed found levels of testosterone in the dorsal vein and in the prostate which were many times higher than the levels measured in normal peripheral blood from the same patient. Related substances in the samples were consistent with the blood having come straight from the testicles. They dubbed this phenomenon “sneaky T”, and describe their results as supportive of the Gat/Goren theory.

If I were just being booster-ish, I could leave it at that (“yay, support”); but I’m taking a hard numerical look. And from a numerical point of view, at first glance that support seems weak. Only 20% of the men had dorsal vein / peripheral vein ratios of testosterone which were two or greater. About half of them had ratios below one. This is not what you’d expect if this were the main driving force of prostate cancer: you’d expect seriously elevated ratios in pretty much all the men, not just in 20% or 50% of them.

The association they found between dorsal vein testosterone and prostate tissue testosterone is also weak. By biology standards it’s totally there (P = 0.004), but there were still a lot of men with high levels in one of those places and low levels in the other. This is not what you want for the definitive mechanical cause of something.

But the title of a paper they cite caught my eye: “Testosterone and estradiol are co-secreted episodically by the human testis.” Looking at it, I find it could explain the above weaknesses: the testicles don’t put out testosterone all the time, but rather do so only in pulses, at the rate of about one pulse per hour. Testosterone stays in the bloodstream long enough that testosterone measurements in circulating blood don’t vary much, but the output of the testicles varies quite a lot. The paper’s measurements (once per fifteen minutes) weren’t frequent enough to really pin down the length of each pulse, and accordingly they give no figures for that length; but eyeballing their graphs, maybe elevated testosterone is present about a quarter of the time, though it’s hard to tell.

So when the Alyamani paper found doubled levels in 20% of men, that could mean that it was actually happening in all of them, just only about 20% of the time in each. Or it might be happening in half of them, about 40% of the time in each. Also, the stress of surgery might have affected the timing of the testosterone pulses.

The pulsing also could explain prostate tissue concentrations often being different from dorsal vein concentrations: testosterone takes time to sink in, so if they measured on the leading edge of a pulse the tissue concentrations would be lower than the vein concentrations, whereas on the trailing edge they’d be higher. Or the measurements might have been done at different times during the course of the surgery; the dorsal vein blood might have been extracted, say, ten minutes prior to the prostate’s extraction.

So the Alyamani paper’s measurements are consistent with backflow of high-testosterone blood being a factor not just in 20% or 50% of cases but in all of them. Still, the backflow, when present, is doubtless stronger in some men and weaker in others. And indeed being in that top 20% did have some predictive value: prostate cancer recurrences were more common in the 20% group. (Since the prostates themselves were all removed, this presumably represents metastases. It would be interesting to know whether the increased metastases were in the same local area bathed by high testosterone or whether they were distant; but the paper does not report this.) They also did not measure free testosterone, just total testosterone, so that’s another unknown.

Besides the BPH paper, Gat and Goren even tried their method on outright prostate cancer (early stage, Gleason 3+3) and report disappearance of cancer (as measured via biopsy) in 5 out of 6 patients, along with lowering of PSA levels.

One thing to note, though, is that their fix of destroying the spermatic vein and any collaterals can’t make the system as good as it was originally. Destroying a backflowing vein always provides improvement in pressures (since otherwise the vein wouldn’t be backflowing), but it can’t improve pressures as much as forward flow would. The ideal would be valve repair or replacement; that is done routinely on heart valves, but not on vein valves. (This also explains why evolution hasn’t simply removed the spermatic vein in us: when it’s there and working, it helps.)

Operations for varicocele are done widely, to try to fix male fertility, but aren’t always of this sort: it’s common to see the swollen veins in the scrotum as the problem and simply remove many of them surgically. This does not squarely address the problem of backflow, and indeed there’s a bit of debate in the medical literature over whether it produces statistically significant fertility improvements. (On the whole it seems to, but there are enough failures to produce debate.)

Even among doctors using the embolization approach (that being the term for inserting a catheter and using it to apply a sclerosing agent), many do it only on the left side, that usually being the one with the visible varicocele. (There is an asymmetry among the spermatic veins, with the left vein being a bit longer and thus more problematic.) Besides doing both sides (or at least checking both sides for backflow with contrast agent), sclerosing each from top to bottom, the full Gat/Goren procedure is also to check for collateral veins and sclerose those too, and then follow up with more contrast agent to ensure that it was done properly.

So there’s a chance that a varicocele surgeon will do this properly, but one can’t just go to a random varicocele surgeon and assume he’ll do it properly. Even someone who does believe the Gat/Goren theory can screw it up in practice, especially if you’ve just got done persuading him and this is his first try.

Screening for this disorder is simple: use a thermal camera and compare testicular temperature sitting up (or standing) versus lying down, in each case waiting five minutes or so for temperatures to equilibrate, and taping the penis up so that it does not affect the measurement. According to Gat and Goren, this is almost as good a test as measuring backflow on fluoroscopy, and a far more sensitive test than trying to look for the enlarged veins of varicocele. (Rather than a thermal camera, they use a liquid crystal strip which is designed and branded for this exact job; but given how expensive medical items are, these days thermal cameras are likely cheaper and are certainly more widely available. Their calibration is probably not as good, though.)

In the above-referenced blog post, Scott Alexander goes on to write that neglect of this sort of new idea isn’t some sort of conspiracy; it’s just the default. For starters, most new ideas everywhere are wrong and deserve to be neglected. And here it’s not like drugs where the patent system incentivizes people to develop new ones and gets them enough money to test them thoroughly and then pay for billions of dollars in advertising. It also is not one of the “hot” fields in science where scientists are racing to study the possibilities. It’s not genomics or the microbiome or any other “-ome”; it’s just plumbing.

He might have added that most of society’s attention on medicine is focused on squabbling about who pays for it, with precious little attention given to possibilities of finding new ways to actually cure disease. Yet those can represent the most dramatic cost savings; here, a thousand-dollar procedure might mean not spending hundreds of thousands of dollars on cancer. The thinking by the powers-that-be should not always be “oh, no, not another thing that we’ll have to spend even more money on”, even when that is true in the short run.

Malpractice law also stacks the deck against innovation: it doesn’t blame doctors for doing what doctors generally believe in doing (the “standard of care”), even if the outcome is bad, but it does blame them in the event of a bad outcome from something new and innovative. (Which in a way it should, since most new ideas are wrong; but it’s never really fair to put only the failures in front of a scientifically ignorant jury and invite them to shell out millions in damages.)

Insurance doesn’t pay for “experimental” treatments, either.

Advertising by doctors is also strongly frowned-on, particularly advertising that goes against conventional wisdom; a doctor who blanketed the local airwaves with claims of a prostate cancer cure (or even a preventative) would very likely get his license yanked by the state medical board. (Not that broadcast advertising really would be the way here: too costly for an individual doctor. The modern way would be targeted Facebook ads, relying on Facebook’s intimate knowledge of personal medical problems. The medical board might not even find out about it, though if they did they likely would be extra wrathful.)

The back-to-nature crowd is also not interested, at least not in the financial sense of “interested”, because there’s nothing here they can sell as a “dietary supplement” and they aren’t permitted to perform medical procedures. Perhaps they could advocate going back to walking on all fours? Nah, too impractical. Going back to the oceans and living like fish, with a supportive pressure gradient all around us? Nah, even more impractical (though there already is a sect of “aquatic ape” believers out there).

None of this amounts to conspiracy – it’s all in the open – but it adds up to quite a set of obstacles. (It’s not like anyone’s paying me to write this, or like I have much prospect of making money from it; it’s just the strong curiosity of someone whose grandfathers both died from prostate cancer.)

Being surgery, this procedure doesn’t need to go through FDA approval, so there’s no decade-long process to form an obstacle to people getting it. Finding a doctor who will do a good job of it, though, is not simple; a short glance at patient forums reveals considerable frustration. I can’t tell if the Gat/Goren clinic in Israel is still open for business: their website www.pirion.co.il isn’t responding, and given those doctors’ ages it wouldn’t be surprising if it has closed. The German clinic which did the 2014 reproducing study might still be doing the procedure. At any rate, though, a single clinic can’t handle worldwide demand for such a common disorder – not even just elite demand.

The procedure also doesn’t last forever, according to Gat and Goren’s latest paper. They write that new venous bypasses grow to replace the destroyed spermatic veins: at first these are tiny, but then grow to where the problem recurs. Part of their reasoning, though, is faulty: they write that at first the size of each growing vein is small enough that capillary action can draw fluid up. Now, it’s quite true that capillary action (the physical/chemical attraction between the fluid and the walls of the capillary tube) can draw fluid up through great heights; trees, for instance, rely on it to draw water into the treetops. But it can only draw fluid up into empty space; it has no lifting effect when the tube starts out completely filled, as is the case here. (In trees it’s the evaporation at the top that powers it.) A simpler explanation is just that those tiny veins are too small to cause the problem to recur. In any case, the paper makes no comment as to whether the problem can be solved the same way a second time; obviously in principle it can, but finding all the new bypasses and sclerosing them might be difficult in practice.

As for mass adoption, I’m well aware that this essay is not the stuff of a mass patient movement. I’ve tried to make it accessible, but the needs of actually being accurate and making a thorough technical argument mean that not more than one in a thousand patients would read to the end of it. (If you think otherwise, please consider that your social circles are not typical.) A video with animations would improve that proportion considerably, maybe to one in a hundred, and I’ve considered it, though I’m not handy with animation tools. But it’ll take serious interest from scientists and doctors to really put an end to all this prostate trouble.